What’s the best way to get started with a big new project? Something like building an open source, serverless, customer deployed, scalable spreadsheet from scratch?

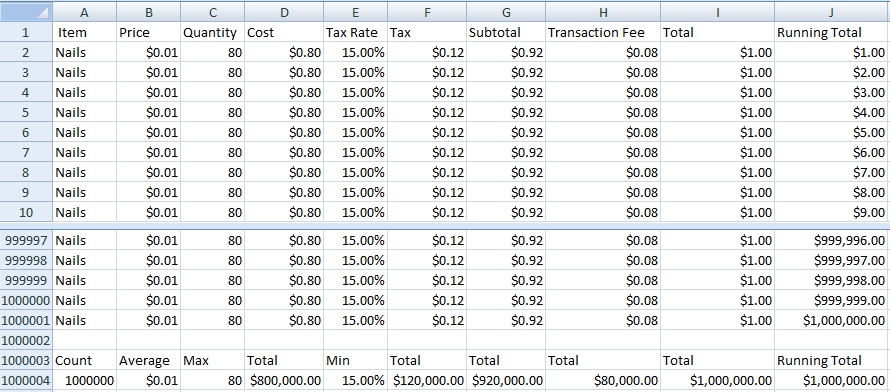

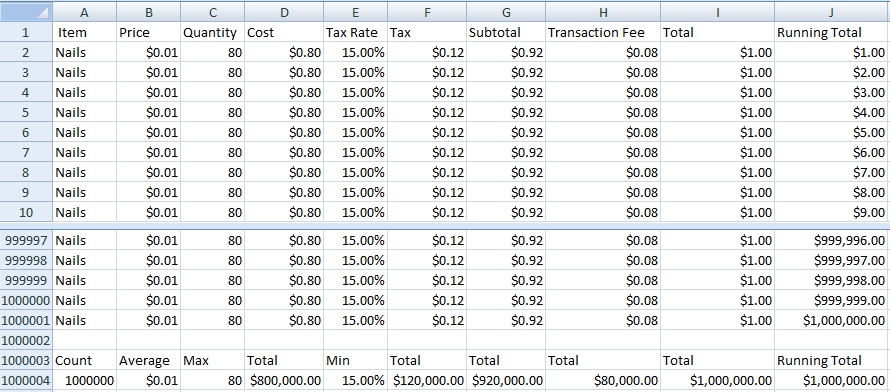

I like to start with a simple motivating example. Something I can get my head round that lets me get a deeper understanding of the problem space. Once I’ve extracted what I can from that I can make it more complex or look at something in a neighboring space. To that end, let me show you round the world’s most boring spreadsheet.

I built it in Excel 2007 running on Windows 11. No Microsoft, I do not want to take up your kind offer of an upgrade to a Microsoft 365 subscription. Excel 2007 was the version that introduced the Office Open XML format still used today, increased limits to 1,048,576 rows and 16,384 columns and introduced a multi-threaded calculation engine. It will do just fine for our purposes.

The spreadsheet is used to track sales for a hardware store. Inexplicably, the store seems to only sell nails and always in the same amounts. The total price for each purchase is worked out as

- Cost = Price * Quantity

- Tax = Cost * Tax Rate

- Subtotal = Cost + Tax

- Total = Subtotal + Transaction Fee

The store owner likes to keep track of a running total in each row which now and then they compare with the overall total to make sure that the spreadsheet “isn’t cheating”. They also calculate count, average, max, min and sums of the other columns.

In all the years the store has been in business, the prices, tax rate and fees have never changed. Perhaps that’s why they’ve been so successful and have just recorded their millionth sale.

That gives us a spreadsheet with 1 million rows and 10 million cells. Right at the limits of what Excel and Google Sheets allow. So, how does it perform?

Surprisingly well. I have a reasonable spec Windows desktop: a Ryzen 5600X with 6 dual-threaded cores, 16GB of RAM and a fast M.2 NVMe SSD. The spreadsheet is 60MB on disk using the default .xlsx format or 20MB in the optimized binary .xlsb format. Opening the spreadsheet takes 10 seconds and requires 400MB of RAM. After that, performance is pretty much interactive. A full recalculation of the entire spreadsheet takes about half a second - just enough time for Excel to bring up a progress bar and report that it’s calculating using 12 threads.

I need to be able to match this level of usability with my cloud based solution. If potential customers can bring in their existing spreadsheets and see them working well, I then get the opportunity to show them the scalability and additional features I intend to deliver. Let’s do a bit of analysis to understand what’s going on here and see if we can pull out some test cases that I can use to benchmark different approaches. Before I do that, I want to take you on a brief detour where I figure out how to accurately measure calculation time.

Timing

The simplest approach is to do it manually with a stopwatch. Unfortunately, my boring spreadsheet is too fast. I don’t want to add pointless busy work to slow things down enough to measure by hand.

What if I could get the spreadsheet to time itself? Excel includes a NOW() function which returns the current date and time. NOW is a volatile function. Every time it’s called it will return a different value - the current date and time. Every cell with a formula that includes NOW() will be recalculated on any change to the spreadsheet. If I can arrange for NOW() to be executed before and after the calculation I want to time, I can determine the time taken in between.

It works. Kind of. You have to make sure that whichever formula is evaluated first has a dependency on the cell with the start NOW() and that the cell with the end NOW() depends on the cells that will be evaluated last. The calculation is multi-threaded so you can’t give the calculation engine any wiggle room if you want accurate results. In addition, at least with my copy of Excel, NOW() only has a resolution of 10ms.

Luckily, I found a better way. While trying to understand how the Excel calculation engine works I stumbled across Microsoft documentation on making workbooks calculate faster, which includes some handy VBA macros for timing calculation performance including full recalc, incremental recalc and recalc of a specified range of cells. Even better, they use the system high-resolution timer for microsecond accuracy.

After all that I can tell you that a full recalculation of the spreadsheet takes 0.57 seconds (there are more decimal places but they vary from run to run).

Analysis

The Excel calculation engine consists of three parts. First, a system that determines and maintains a dependency graph between cells. As the user modifies values in the spreadsheet the corresponding cell and all cells that depend on it are marked as dirty (needing recalculation). As formulas are edited, the dependency graph is updated to match.

Second, a system that uses the dependency graph to determine which formulas need to be calculated in which order (the “calculation chain”). Excel doesn’t update the calculation chain as the spreadsheet is edited. Instead, it updates it dynamically during the calculation process. It starts with the calculation chain used last time and if it encounters a formula with dependents that are still dirty, it moves the formula further down the chain.

Finally, there’s the system that calculates all the formulas and updates the values in the corresponding cells. Each formula for a dirty cell is calculated in calculation chain order. The cell value is updated and the cell marked as complete.

For now, we’re going to treat the first two systems as a black box and focus on the calculation of the formulas.

Each row has five simple formulas involving two multiplies and three adds. Each depending on two input cells. Overall that makes 10 million reads, 5 million floating point operations and 5 million writes.

The summary row uses COUNTA, AVERAGE, MAX, MIN and five SUM functions over one million data rows.

COUNTA- One million reads, one million increments, one write.MIN,MAX- One million reads, one million comparisons, one write.SUM- One million reads, one million additions, one write.AVERAGE- One million additions, one million increments, one divide, one write.

That makes a grand total of 19 million reads, 15 million floating point operations and 5 million writes for a full recalculation. Adding a new row calculates values for that row and recalculates the summary row. Which requires 14 formula evaluations, 9 million reads, 10 million floating point operations and 20 writes.

If you’re like me, you may be wondering if Excel really adds up a column of a million numbers from scratch if just one of those numbers changes. And yes, it really does. The time taken (0.017 seconds) is the same whether one value or all values have changed. If you do the same thing on a spreadsheet with one hundred thousand rows, it takes a tenth of the time.

Similarly, there is no common subexpression elimination, either within a single formula or across formulas. The first recommendation in Microsoft’s guidance for optimizing spreadsheets is to move repeated calculations and intermediate results into their own cells so that the calculated values can be reused.

There’s no hidden magic to formula calculation. The calculation is performed literally as written. When all your data is directly accessible in memory, its amazing how well brute force can work.

Of course these are all simple formulas with O(n) complexity. My initial version of the spreadsheet tried to determine the number of distinct item values. Perhaps the store owner wants to be sure they notice if they ever sell something other than nails. There’s no built in function that provides a distinct count. Like most people, I turned to Google and found the standard Excel idiom for this task: SUMPRODUCT(1/COUNTIF(range,range)).

Seems simple enough. That repeated range looks a bit weird but what’s the worst that can happen?

If you try this on a spreadsheet with more than a few thousand rows it will lock up and hang as it tries to recalculate. This formula is O(n2). Each cell in the range is compared with the value of every other cell in the range. In my case that’s a million comparisons per cell repeated a million times. Each step operates on an array of a million counts which are then inverted and summed together at the end.

Test Cases

I’ve got what I wanted out of this exercise. I have a better understanding of how spreadsheets work and some simple test cases I can use to benchmark possible approaches to implementing my cloud spreadsheet.

| Test Case | Reads | Formulas Evaluated | Floating Point Operations | Writes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Import | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10,000,030 |

| Full Recalc | 19,000,000 | 5,000,010 | 15,000,001 | 5,000,010 |

| New Row | 9,000,005 | 14 | 10,000,006 | 20 |

| Sum Column | 1,000,000 | 1 | 1,000,000 | 1 |

| Running Total | 2,000,000 | 1,000,000 | 1,000,000 | 1,000,000 |

| Edit First Row | 10,000,010 | 1,000,013 | 10,000,006 | 1,000,013 |

| Distinct Idiom | 1,000,000,000,0000 | 1 | 2,000,002,000,0000 | 1 |

| Export | 10,000,030 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

I should be able to import my boring spreadsheet as is and do a full recalculation to validate that it’s working. Inserting a new row will be a frequent operation and should be quick and easy. To support that I need a scalable way of summing a column (or performing any other simple O(n) function). I need to handle cases with long chains of dependent formulas like the running total column. My users will also want the confidence that they can export their spreadsheet at any time and go back to Excel or Google Sheets.

What’s the most amount of work I can trigger with a simple change? Try editing quantity in the first row. The spreadsheet needs to recalculate that row, then update everything in the running total column and all but the first summary column. It’s amazing to me that changing a single cell can trigger the evaluation of a million formulas resulting in 10 million reads, 10 million floating point operations and a million writes. And as far as the user is concerned it all happens instantly.

What about the distinct idiom? At a minimum I need to fail gracefully if I encounter O(n2) (or worse) formulas that can’t be calculated in a reasonable time. My spreadsheet certainly can’t hang while it racks up a ridiculous AWS bill. Long term, I need to come up with some way for users to achieve common tasks like this at scale.

Coming up next time: let’s brainstorm some ideas and benchmark them against our test cases.