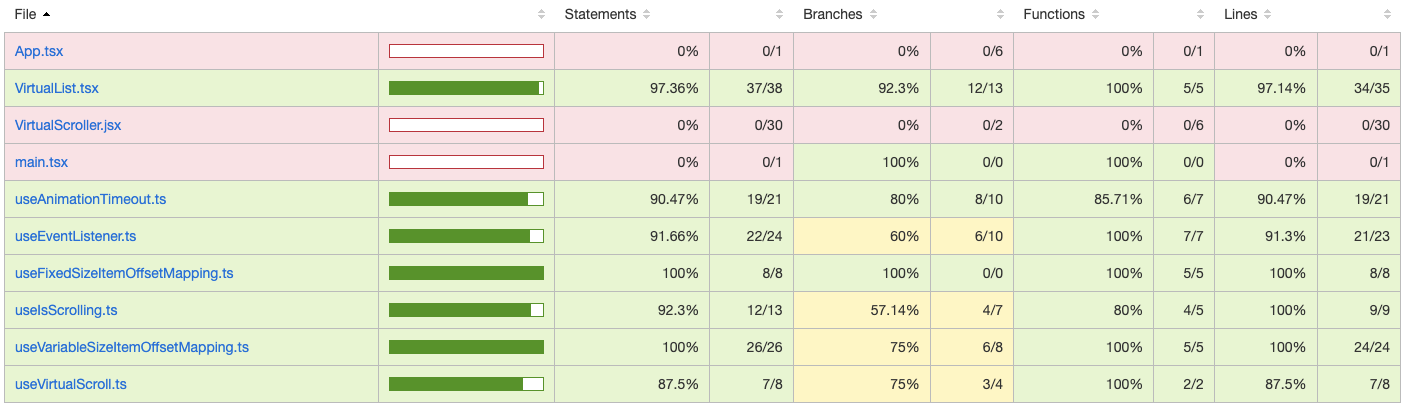

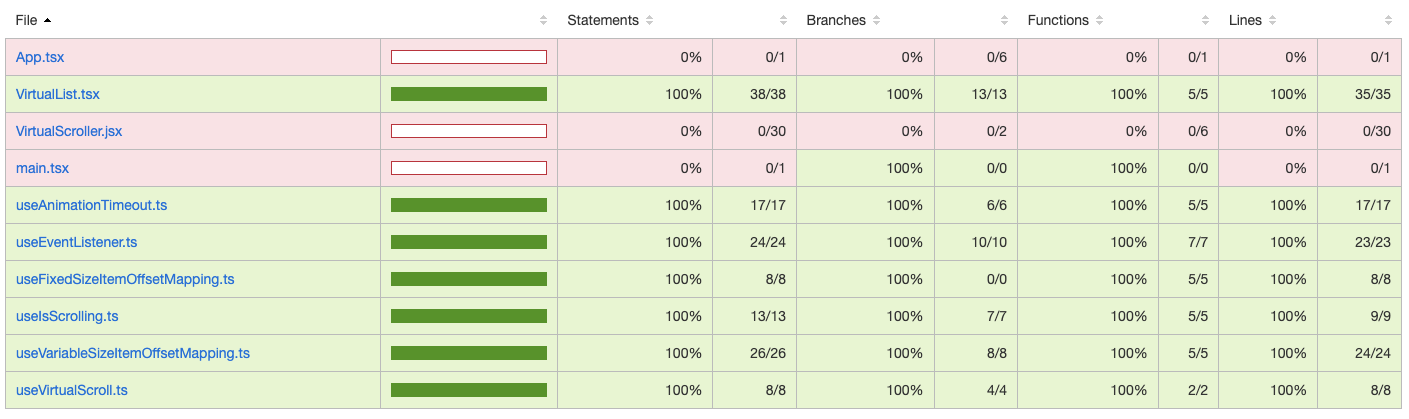

Last time we achieved a significant increase in code coverage by unit testing the effect of scroll events. As a reminder, here’s what our coverage looked like when we finished up.

Apart from a few edge cases, the main thing left to test is my fallback timeout implementation if the scrollend event isn’t implemented or goes missing. To do that we’ll need to mock up a missing scrollend implementation.

Setup

A lot of what I’ll be doing is validating edge cases in my custom hooks. It’s easier to do that in a lower level, more targeted unit test. I added useIsScrolling.test.ts.

I started off with a basic test that mirrors what my component level test is doing. Sending a scroll event so that useIsScrolling() returns true, and then sending a scrollend event so that it returns false.

it('should be true on scroll and false on scrollend', () => {

const { result } = renderHook(() => useIsScrolling())

expect(result.current).toBe(false);

{act(() => {

fireEvent.scroll(window, { target: { scrollTop: 100 }});

})}

expect(result.current).toBe(true);

{act(() => {

fireEventScrollEnd(window);

})}

expect(result.current).toBe(false);

})

I also get to cover one of the outstanding edge cases by running the hook on the DOM window, which is the default target for useIsScrolling.

Mocking Undefined

My useIsScrolling implementation uses ('onscrollend' in window) to determine whether the DOM supports the scrollend event. My first job is to mock window so that its onscrollend property is undefined.

I had to bounce between the Vitest and Jest documentation. Vitest documentation lacks detail. It claims to have a Jest compatible API, so I went to the Jest docs for the missing detail.

The replaceProperty API looks like it will do what I want. Unfortunately, it doesn’t exist in Vitest. Apparently there are a few differences in their Jest compatible API.

The Vitest Migration Guide suggests using vi.stubEnv or vi.spyOn instead. The former will mock environment variables, the latter will mock the return value from a getter function. However, I want the property itself to appear undefined.

A trawl through the entire Vitest API eventually turned up vi.stubGlobal. At first glance it only lets you stub global variables. However, the description suggests that with jsdom someGlobalVariable and window.someGlobalVariable are equivalent. Let’s try it out.

describe('useIsScrolling undefining onscrollend', () => {

afterEach(() => {

vi.unstubAllGlobals();

})

it('should fallback to timer if scrollend unimplemented', () => {

vi.stubGlobal('onscrollend', undefined);

...

})

})

It does override window.onscrollend but all it does is change the value of the property from null to undefined. The property still exists. I did consider changing my implementation in useIsScrolling to explicitly check to see if onscrollend had been set to undefined but that seems like cheating. It doesn’t make any sense to include that in production code.

I dug into how Vitest implements global stubbing. It’s very simple. It uses Object.defineProperty to set the value of the property and records the original value in a global map. If the property didn’t previously exist it uses Reflect.deleteProperty to remove it in unstubAllGlobals.

I can write my own version that actually deletes the property if asked to undefine it, and make it work for any object property like Jest’s replaceProperty API. Putting it all together, we end up with this.

describe('useIsScrolling undefining onscrollend', () => {

afterEach(() => {

unstubAllProperties();

})

it('should fallback to timer if scrollend unimplemented', () => {

stubProperty(window, 'onscrollend', undefined);

const { result } = renderHook(() => useIsScrolling())

expect(result.current).toBe(false);

{act(() => {

fireEvent.scroll(window, { target: { scrollTop: 100 }});

})}

expect(result.current).toBe(true);

// Wait long enough ...

expect(result.current).toBe(false);

})

})

Which of course fails. The timeout hasn’t fired by the time the test ends. How do we handle that? The naive thing would be to actually wait. In a C style language you could throw in a sleep(1000).

In Javascript you have to rely on asynchronous code, not least because the timeout won’t be delivered until execution returns to the event loop. With async/await semantics in modern Javascript it doesn’t look too different once we’ve implemented sleep by wrapping a promise around setTimeout.

function sleep(delay: number) {

return new Promise(resolve => setTimeout(resolve, delay));

}

it('should fallback to timer if scrollend unimplemented', async () => {

stubProperty(window, 'onscrollend', undefined);

const { result } = renderHook(() => useIsScrolling())

expect(result.current).toBe(false);

{act(() => {

fireEvent.scroll(window, { target: { scrollTop: 100 }});

})}

expect(result.current).toBe(true);

await sleep(1000);

expect(result.current).toBe(false);

})

Which surprisingly, actually works. However, it has some serious problems. The test now depends on wall clock time which can easily make for non-deterministic flaky tests.

To reduce the chance of failing, you need to make the delay longer. Which is where you run into the other serious problem. Your tests will take ages. My test reruns have gone from 200ms to 1.2 seconds and I’ve only added a single time based test.

You also generate warnings from React because the timeout triggered by the async sleep modifies React state without being wrapped in an act. We can fix that, but need to use the async version of act.

await act(async () => { await sleep(1000); });

Mocking Time

The right way of doing this is to mock time. Vitest uses an embedded copy of @sinonjs/fake-timers for its time mocking functionality. The standard JavaScript time related APIs are mocked to depend on a fake internal clock which you can control in your unit test. There are both synchronous and asynchronous versions of the APIs for advancing time. If we use the synchronous ones we can go back to a simple synchronous unit test.

The Vitest docs include a list of time related functions that are mocked. Unfortunately, the three we depend on (requestAnimationFrame, cancelAnimationFrame and performance) are not on the list.

According to the fake-timers README, it supports setTimeout, clearTimeout, setImmediate, clearImmediate,setInterval, clearInterval, Date, requestAnimationFrame, cancelAnimationFrame, requestIdleCallback, cancelIdleCallback, hrtime, and performance by default.

Which documentation is right? Let’s try it and see.

it('should fallback to timer if scrollend unimplemented', () => {

vi.useFakeTimers();

stubProperty(window, 'onscrollend', undefined);

const { result } = renderHook(() => useIsScrolling())

expect(result.current).toBe(false);

{act(() => {

fireEvent.scroll(window, { target: { scrollTop: 100 }});

})}

expect(result.current).toBe(true);

{act(() => {

vi.advanceTimersByTime(1000);

})}

expect(result.current).toBe(false);

})

Sadly it didn’t work. Diving in with the debugger shows that requestAnimationFrame is invoking its callback. The callback uses performance.now to see whether enough time has elapsed but it hasn’t.

I tried replacing vi.advanceTimersByTime with vi.runAllTimers. It repeatedly invokes timer callbacks until there are none left. That results in requestAnimationFrame being called a thousand times before Vitest detects an infinite loop and fails the test.

It looks like performance hasn’t been mocked. Further exploration with the debugger confirms that Vitest only mocks a subset of the available timers by default. In particular, setTimeout, clearTimeout, setImmediate, clearImmediate,setInterval, clearInterval, and Date.

Which is weird in two ways. First, why not mock all the time related APIs by default? Second, why is my requestAnimationFrame callback being invoked if requestAnimationFrame hasn’t been mocked?

The second question is easy to answer using the debugger. jsdom internally implements requestAnimationFrame using setInterval.

The first question is covered by a Vitest known issue. Apparently, Vitest’s default list was copied from the fake-timers README when the feature was implemented. As fake-timers functionality improved, the defaults weren’t updated. Changing them now might cause backwards compatibility issues, so the maintainers haven’t touched it. However, they did have the helpful suggestion of fixing the problem by updating the defaults in your project’s vite.config.ts file.

fakeTimers: {

toFake: [...(configDefaults.fakeTimers.toFake ?? []), 'performance'],

},

The Vite command line watch sorted itself out as soon as I saved the updated config file and all tests passed. I needed to restart Visual Studio Code before the tests run by the Vitest plugin would pass. After that I added one more test to cover the case where scrollend is supported but the event goes missing.

I thought I was done but I hit one final problem. I was playing around in Visual Studio Code, running individual tests, when suddenly one of my VirtualList tests started failing. I hadn’t changed any code and the test ran OK in the command line Vitest. My first thought was flakiness in the Vitest plugin.

I finally realized that the failure was consistent with fake timers leaking into other tests. However, I had an afterAll clause that removed all mocking. How could it be going wrong?

It turned out to be another documentation problem. The example code for timers in the Vitest guide suggests that restoreAllMocks will also cleanup timers. Not so. Each mocking feature in Vitest is independent. There is no “cleanup everything” API. You have to match useFakeTimers() with useRealTimers().

Conclusion

Getting mocking working was more involved that I thought it would be. There’s a recurring theme that Vitest documentation is inadequate so you have to look at the original documentation for features embedded in Vitest, then find unnecessary differences in the Vitest implementation.

On the positive side, Vitest is still fast and feature rich. I didn’t run into anything insurmountable, just annoying fit and finish issues.

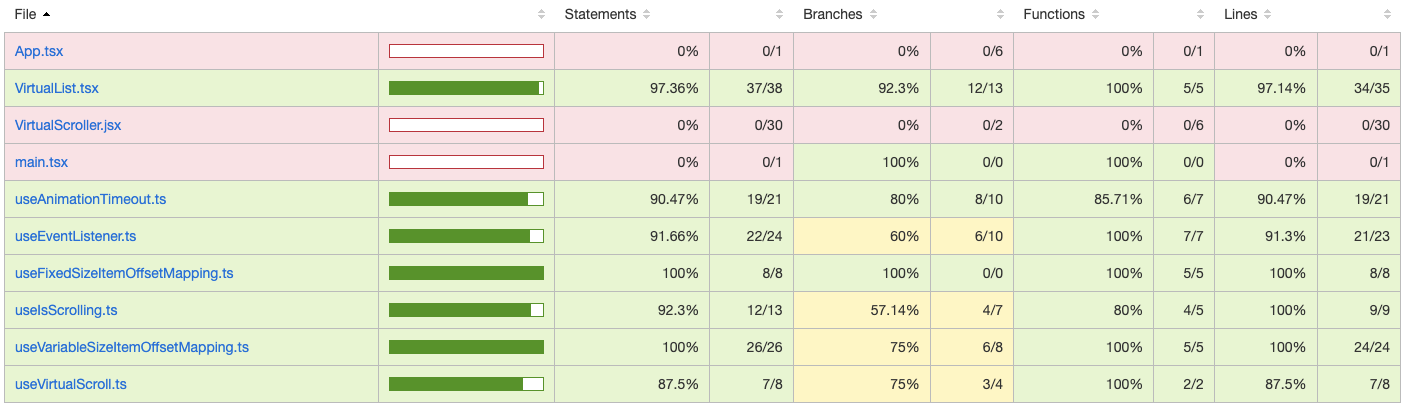

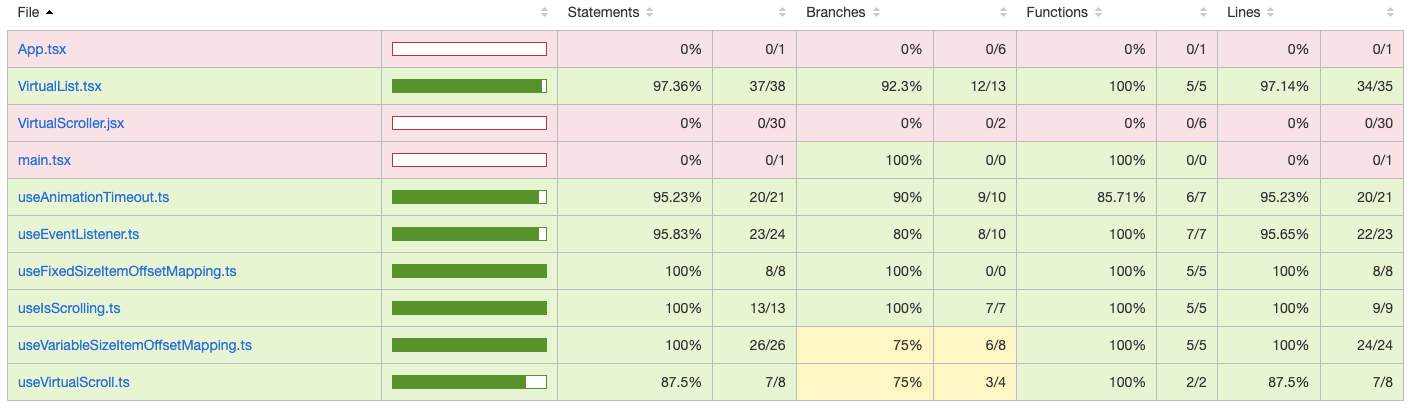

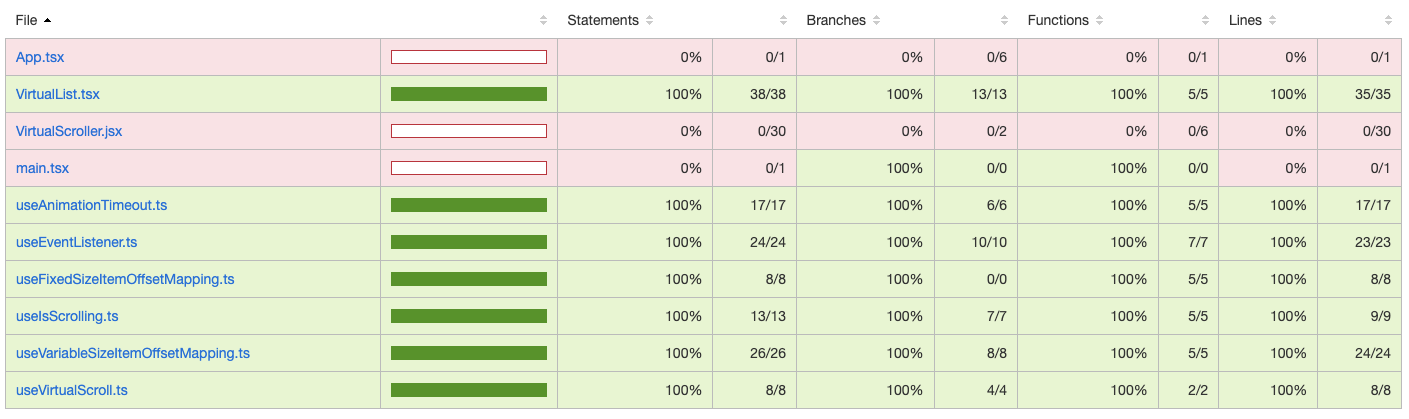

How’s the coverage looking? I’m glad you asked.

We got useIsScrolling coverage up to 100% across the board, including all branches. The two dependent hooks, useEventListener and useAnimationTimeout have hit over 95% statement coverage.

Edge Cases

What’s left to do? Just edge cases.

- Test rendering an empty VirtualList.

useAnimationTimeouthas a fallback forperformance.nowthat will never be used. It was copied from the original code in the react-window project. The code can only be used in a browser context and all major browsers have supportedperformance.nowsince 2014. I just need to remove the pointless fallback.useEventListenerhas uncovered branches that handle being called with a default argument and being called with a React ref to a null element.useVariableSizeItemOffsetMappinghas a couple of uncovered branches- Variable size item list with less items than the list of variable sizes

- Variable size item list with no variable sizes

useVirtualScrollhas an optimization applied when it receives a scroll end but the scroll position hasn’t changed. It’s not covered by any of the existing test cases.

It took me an hour to work through all these. This time everything worked first time. I even got to make use of another mocking feature. Creating a mock event handler that made it easy to verify that it was invoked.

function handler(_: Event) {};

const mock = vi.fn().mockImplementation(handler);

renderHook(() => useEventListener('scroll', mock));

act(() => { fireEvent.scroll(window); });

expect(mock).toHaveBeenCalled()

100% Coverage

Mission accomplished. 100% coverage across the board (for the files I’m actually testing).

Does that mean my code is fully tested? Of course not. Every statement and branch is invoked by my tests but that doesn’t tell me whether the code is correct. It also doesn’t mean that every possible path through the code, every possible combination of branches has been covered.

Coverage is a useful tool to highlight areas of code that your tests go nowhere near. You still need good judgement to decide how detailed your tests need to be. You need to strike the right balance between writing actual code, writing and maintaining unit tests, and manually testing.

Next Time

Next time, we’re back to writing actual code. Now that we have a unit test framework in place, maybe we can try doing it in a Test Driven Development style?