Remember how we used to build web apps? A database, some app servers and a load balancer. What we’d disparagingly call a Monolith today.

Maintaining consistent state is really easy. All your data is in one place. Design a good schema with appropriate constraints. Wrap updates in a transaction. The data is always consistent, operations either happen completely or not at all. Expose access via a simple REST API. A request comes in, you hit the database, then return a response when the database is done.

Unfortunately, things rarely stay so simple. What starts out as a simple monolith soon becomes a complex monolith with lots of additional state bolted onto the side. What was a complex monolith gets split up into multiple microservices, with application state distributed between them. What was a simple microservice becomes a complex microservice with lots of additional state bolted onto the side.

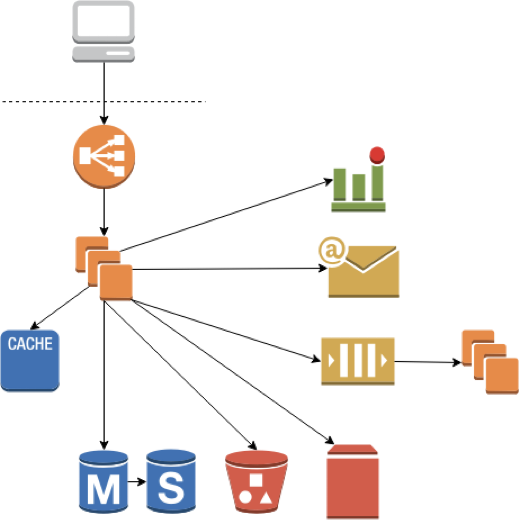

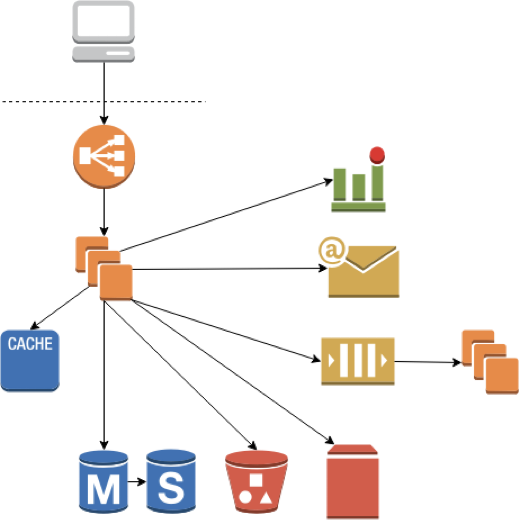

Maybe you’ve added a cache, or are storing blobs of data in S3. Perhaps you need to interact with a third party service or a downstream microservice. You may need a subsystem to manage long running background jobs. Now when a request comes in, you have to update the database, write part of the incoming data to S3, start a background job, notify a downstream service and update the cache.

The database is still the main source of truth but you have all these side effects that need to happen as well. How do you make sure all the things that need to happen actually happen? How do you ensure that all that distributed state is eventually consistent?

Keep It Simple Stupid

The approach that everyone starts with is to add the logic needed to the app server. Don’t think about it too much. Add the code where it’s convenient. Mix database updates and side effects. Wrap the whole thing in a transaction so the database update is atomic and consistent. Simple, quick to write, easy to understand and maintain. Works most of the time.

Uploading a file might look like :

- Start database transaction

- Update file metadata in database

- Write file content to S3

- Call permissions service to register the new file

- Save permissions service id in our database

- Create a background job to generate a file thumbnail

- Update cache with file metadata and thumbnail location

- End database transaction

Error handling tends to be piecemeal and ad hoc. What happens if the permissions service returns an error (even after a few retries)? Abort the transaction? What about that blob of data we wrote into S3? I guess we should try and delete it. Can that fail?

Everything fails

Werner Vogels, CTO, AWS

One of the first web apps I worked with was built this way. It was a complex monolith with a ton of features, including a file store. There was this weird bug where the app showed that a file existed but when the user tried to download the content, the data wasn’t there. Everyone was pulling their hair out, trying to work out how blobs of data could just vanish.

The sequence of events was pretty simple. A user would attempt to delete a file. Everything worked until the final step of committing the database transaction. There was some conflict and the transaction failed. The database rolled back the deletion of the file metadata. Unfortunately, there was nothing to rollback the side effect that deleted the separately stored file content.

Side Effects Come Last

Once you’ve played whack-a-mole a few times, you’ll try to add some more structure. Another app that I worked with had a custom app framework that everyone used. You could write your business logic in a familiar ad hoc style, mixing database updates and side effects. The framework didn’t perform the side effects immediately, instead it queued them up. If the database transaction completed successfully, it would trigger all the side effects. If the transaction failed, the side effects were discarded.

What if the downstream service we need to call as a side effect is down? The framework included a background job system. Any side effect that was potentially long running or might need to cope with an external outage could be specified to run as a background job.

Problem solved, right? Not quite. There’s a small window of vulnerability between completing the database transaction and triggering the side effects. What happens if the app server dies in between? What happens if the background job system is unavailable?

Sounds pretty unlikely. If we have good logging and monitoring we can spot the rare cases when something goes wrong and fix things up manually. Which is workable, pragmatic even. Until you start to scale the system up.

Everything fails, all the time

Werner Vogels, CTO, AWS

When you scale up, rare failures become common. What was exceptional, is now normal. Part of the day to day. Any lurking edge cases that you’ve ignored or deal with manually will become intolerable until you fix them properly.

Another app I worked with reduced the window of vulnerability to the bare minimum. They used a separate, highly resilient workflow system to run all the side effect logic. They used a highly available, resilient queue to connect the app servers and the workflow system. Once the database transaction successfully completed, all the app server had to do was add a message to the queue. Worked great during development, internal testing and beta testing.

The app was popular. We onboarded hundreds of customers, some with hundreds of users. Customer complaints increased. Varied reports but all with a similar root cause. The database had been updated but the side effect workflow hadn’t run.

What went wrong? Everything.

Turns out that app servers will occasionally crash at the most inconvenient moment. The highly available queue was also highly complex. There were bugs in the language library used by the app server to add messages to the queue, other bugs in the different language library used by the workflow system to read messages from the queue. Fundamental misunderstandings of the contract between queue and client that in theory assured high availability and resilience. Outages in the queueing service itself.

Even worse, there was no easy way to detect which workflows hadn’t run. There was no difference in the database between a transaction whose side effects completed and one that didn’t. In many cases you couldn’t work out what side effects needed to be run from what changed in the database. You would have to scan through every record in the database performing a cross-service join to check that everything was consistent. Or, just wait for your customers to report problems and fix them reactively.

Eventual Consistency

There was another problem even when the system worked as designed. The side effects would run and eventually things would be consistent. Unfortunately, the UX designers on the product didn’t understand the implications of eventual consistency. They were used to desktop applications and simple monoliths where changes effectively happen instantly and consistently.

There was no provision in the UX for inconsistent state. You couldn’t see whether workflows were still running or what the state of progress was. When workflows were partially complete, the app would often behave … poorly.

You allow things to be inconsistent and then you find ways to compensate for mistakes, versus trying to prevent mistakes altogether.

Eric Brewer, VP Infrastructure, Google (Author of CAP theorem)

There is no strict consistency in the real world. You often see the motivating example of a bank transfer as the reason why strict consistency is needed. That’s not how it works in the real world. The financial system is not based on consistency, it’s based on auditing and compensation. The money gets added to one account before it gets removed from another. If the check bounces, they take the money back.

The Single Write Principle

Let’s assume that our UX designers will eventually get their heads round designing for eventual consistency. That leaves us software architects and engineers with the problem of ensuring that state does eventually become consistent.

I’ve seen lots of different solutions and the ones that worked had one thing in common. Making updates to state spread across multiple services and data stores inevitably requires multiple write operations. Each individual write is atomic but the overall process is not. The key to making the whole process reliable is to have one single write that acts as the linchpin.

Most of the activity that takes place before the linchpin write is checking business logic constraints to ensure that the overall operation is valid. Any other writes that happen before the linchpin write must be discardable. Their effects should not be visible to other clients. However, they should be discoverable by the system. If the app server crashes before the linchpin write, a recovery process should be able to discard whatever changes were made.

The linchpin write is the point of commitment. The overall operation is safe to apply. This is the point where changes to application state first become visible to other clients. The linchpin write should capture the complete intent of the operation. If the app server crashes after the write completes, a recovery process can read back the linchpin update and use what was written to complete the rest of the operation.

All changes after the linchpin write are side effects that will eventually complete. There may be temporary outages that increase the time needed to achieve consistency. There is no way to rollback the operation after the linchpin write is successful. All possible side effect outcomes must lead to a valid and consistent state.

In our example of a bank handling a check, the linchpin write is adding the funds to the recipient’s account. One of the side effects is forwarding the check to the sending bank to request removal of the funds from the sender’s account. If the sender has insufficient funds, there is no way to rollback the overall operation. Instead, the bank applies a new compensating operation to take the money back from the recipient’s account.

All the different states involved need to be correctly handled by the banking app’s UX. For example, the credited funds may be shown as pending until the overall operation is complete.

Single Write File Upload

That all sounds good in theory. How do you make it work for the file upload example? There are two significant writes - file metadata into a database and the file content into S3. On top of that, there’s a separate permissions service that needs to know about the file for it to be accessible.

The first job is to identify the linchpin write. If you have a primary database, it will almost always be the transaction that commits changes to the database. Then you need to figure out what needs to happen before the linchpin write in order to validate business logic and ensure that you have a reasonable initial state when the linchpin write completes. Try to minimize what you have to do here. You should execute as much as you can as side effects.

A reasonable initial state for a file upload is that the file is visible (file metadata written to the database), accessible in the permissions system and downloadable. It’s OK if a file thumbnail is not immediately available or if the cache is not immediately populated.

Discardable Writes

The key to making this work is that the upload of the data to S3 and registration of the file in the permission system need to be discardable writes. The first requirement for a discardable write is that the data should not be visible to other clients. That’s easy to satisfy. Until the file metadata is added to the database, there’s no way for another client to find the blob of data in S3 or a stub permissions system entry.

The other requirement is that the writes are discarded if the operation fails to complete. The simplest implementation is when the service you’re writing to, like S3, supports lifecycle management rules. The discardable write creates a data object that is tagged so that it automatically deletes itself after a set time period. Unless you’re dealing with high volume writes you would normally give yourself a few days grace period. If the linchpin write succeeds, a follow up side effect removes the auto-delete tag.

Resilient Side Effects

How do we make sure that the side effects actually happen? It would be awful if the file content auto-deleted itself because we didn’t remove the tags. The simplest implementation is one where your database has a reliable way of triggering business logic when a write happens. This feature is commonly known as Change Data Capture. A reliable implementation will repeatedly retry until the business logic confirms that all side effects have completed.

An alternative, if your database supports complex transactions, is to create a pending side effects table. As well as updating file metadata, the linchpin write can add entries to the pending side effects table. As the app server processes each side effect, it removes it from the table. A recovery process runs in the background, looking for pending side effects that have been waiting too long, then executing them if needed.

In both cases there’s a chance that a side effect will be executed more than once (better than a chance that a side effect will never be executed). Side effects should be idempotent. They should be designed so that the end result is the same whether they have been run once or multiple times.

Three Part Recipe

We end up with a three part recipe. Steps 1-6 are the business logic checks and discardable writes, 7-9 is the linchpin write and 10-13 are idempotent side effects.

- Client requests location to upload file content

- App server checks user has permission to upload file and returns S3 signed URL for an auto-delete S3 object

- Client uploads content to S3

- Client calls app server to confirm file upload is complete

- Call permissions service to register new file with auto-delete

-

Invalidate any cached data for file

- Start database transaction

- Update file metadata in database including S3 object id and permissions registration id

-

End database transaction

- Call permissions service to remove auto-delete tag

- Call S3 to remove auto-delete tag

- Update cache with file metadata

- Create a background job to generate a file thumbnail and update file metadata and cache

Coming Up

Next time we’ll take what we’ve learnt and apply it to ensuring that snapshots are actually created, as events are added to the event log of our Event Sourced Cloud Spreadsheet.