I’m a strong believer in unit tests. I try to get close to 100% code coverage with my tests. Which means I have a lot of unit test code. Normally, you try to minimize duplication, and Don’t Repeat Yourself. That has it’s own special challenges when it comes to unit tests.

Unit Test Code

Unit test code is a very particular thing. It’s shaped by the particular unit test framework you’re using. In my case that’s Vitest. The framework provides an API for describing test suites, test cases and assertions of expected behavior.

Here’s an individual unit test I created recently for an asynchronous event log component. Here describe, test and expect are provided by the Vitest API. The test creates an empty event log and then runs a variety of queries that check whether the implementation has the expected behavior.

describe('SimpleEventLog', () => {

test('should start out empty', async () => {

const data = new SimpleEventLog;

let result = await data.query('start', 'end');

expect(result.isOk());

let value = result._unsafeUnwrap();

expect(value.startSequenceId).toEqual(0n);

expect(value.isComplete).toEqual(true);

expect(value.entries.length).toEqual(0);

result = await data.query('snapshot', 'end');

expect(result.isOk());

value = result._unsafeUnwrap();

expect(value.startSequenceId).toEqual(0n);

expect(value.isComplete).toEqual(true);

expect(value.entries.length).toEqual(0);

result = await data.query(0n, 0n);

expect(result.isOk());

value = result._unsafeUnwrap();

expect(value.startSequenceId).toEqual(0n);

expect(value.isComplete).toEqual(true);

expect(value.entries.length).toEqual(0);

result = await data.query(0n, 5n);

expect(result.isOk());

value = result._unsafeUnwrap();

expect(value.startSequenceId).toEqual(0n);

expect(value.isComplete).toEqual(true);

expect(value.entries.length).toEqual(0);

result = await data.query(5n, 30n);

expect(result.isErr());

let err = result._unsafeUnwrapErr();

expect(err.type).toEqual("InfinisheetRangeError");

result = await data.query(-5n, 0n);

expect(result.isErr());

err = result._unsafeUnwrapErr();

expect(err.type).toEqual("InfinisheetRangeError");

})

})

The code is also shaped by the tooling used to run the tests. When a unit test fails you want the cause to be as obvious as possible. That encourages simple, sequential code. The tooling reports an error on a particular line in the test. If that’s buried inside nested loops, or at the bottom of a callstack of function calls, it’s going to be hard to figure out what happened.

The downside is that unit test code can easily become verbose and repetitive. We want to find a sweet spot where we have just enough abstraction to keep our tests understandable and maintainable. Let’s look at some possible solutions for Vitest.

Shared Utilities

Any code that doesn’t directly interact with unit test framework APIs can easily be extracted as a shared utility. This is just regular code. All the normal rules apply.

For example, when testing React components with the jsdom environment, I need to mock browser layout behavior, which in turn means overriding layout related properties in the DOM.

export function overrideProp(element: HTMLElement, prop: string, val: unknown) {

if (!(prop in element))

throw `Property ${prop} doesn't exist when trying to override`;

Object.defineProperty(element, prop, {

value: val,

writable: false

});

}

I extracted a handy utility function that I can use in all my React component test suites.

Setup and Teardown

Most frameworks include Setup and Teardown hooks. You can provide a setup function that runs before every test in a test suite and a teardown function that runs after every test.

describe('VirtualSpreadsheet', () => {

let mock;

beforeEach(() => {

mock = vi.fn();

Element.prototype["scrollTo"] = mock;

})

afterEach(() => {

Reflect.deleteProperty(Element.prototype, "scrollTo");

})

Here I use Vitest’s beforeEach and afterEach hooks to install and remove a mock scrollTo method on DOM elements. I stash the mock function in a variable that’s accessible to all tests in case they need to check whether the mock was called.

I tend to use this approach only when there is cleanup code that has to run after each test. Anything more than single line setup code is best extracted as a utility function. If there’s no cleanup needed, I prefer calling the utility function explicitly at the start of each test, making it clearer what’s going on.

Fixtures

Fixtures are a more sophisticated form of setup and teardown hooks. A fixture typically takes the form of an object that the test interacts with. Unit test frameworks will set up the fixtures needed for each test, make them available to the test and then tear them down after each test.

Vitest supports fixtures using the same approach as Playwright. The Vitest documentation has some gaps that assume you’re familiar with Playwright fixtures. I had to read the Playwright documentation before I fully understood what was going on.

In Vitest, fixtures are part of the test context object. The test context is provided to every test as an optional argument. You define additional fixtures by creating a custom test. Let’s turn our mock scroll function into a fixture.

import { test as baseTest } from 'vitest'

export const test = baseTest.extend({

scrollMock: async ({}, use) => {

const mock = vi.fn();

Element.prototype["scrollTo"] = mock;

await use(mock);

Reflect.deleteProperty(Element.prototype, "scrollTo");

}

})

There’s a lot going on here. You call extend on the base test and pass in an object. Each fixture is defined as a property whose value is an async function. The function has two required arguments. The first is a test context. The fixture can access anything it needs, including other fixtures. The second argument is a use callback function. Your fixture implementation should run any setup code needed to initialize the fixture, pass the fixture to use and await it, then run any teardown code.

You can define as many fixtures as you like. You can also extend an existing custom test to add more fixtures. You would typically have shared utility code that defines all the fixtures needed for your project. You then import your custom test into each unit test file and use the fixtures in your tests.

describe('My Test Suite', () => {

test('needs mocked scroll', async ({ scrollMock }) => {

...

expect(scrollMock).toBeCalledTimes(1);

}

})

There’s lots of magic happening behind the scenes. Fixtures are only initialized if they’re used. You should use object destructuring to retrieve the fixtures from the context. The getters accessed when destructuring run the corresponding fixture functions (recursively if they depend on other fixtures), returning whatever was passed to the use callback. Once the test completes, the functions are resumed so they can cleanup.

So far, I’ve had no compelling need for fixtures. Most of my tests create a single “fixture” (SimpleEventLog in my initial example) that doesn’t need any explicit cleanup. It’s easier to start each test with an explicit single line fixture creation.

Context Properties and Projects

You can also extend the test context with regular properties. Anything that isn’t a fixture is just added to the context where it can be accessed by each test.

export const test = baseTest.extend({

baseURL: '/dev'

})

This becomes useful for code reuse when combined with Vitest projects. You can define multiple projects which include a common set of unit test files. You can override context properties on a per project basis. For example, you could run the same backend test suite against production, staging and dev environments using three projects with a different base URL context property for each.

It’s good to know that this kind of large scale reuse is possible, but at the moment my code reuse needs are more fine grained.

Refactoring Common Code

In particular, I run the same set of assertions for every query in my event log unit test. If it was any other sort of code, I’d refactor it and extract a common expectQueryResult function. What happens if I do that here?

function expectQueryResult(result: Result<QueryValue<LogEntry>, QueryError>,

startSequenceId: SequenceId, isComplete: boolean, length: number) {

expect(result.isOk());

let value = result._unsafeUnwrap();

expect(value.startSequenceId).toEqual(startSequenceId);

expect(value.isComplete).toEqual(isComplete);

expect(value.entries.length).toEqual(length);

}

describe('SimpleEventLog', () => {

test('should start out empty', async () => {

const data = new SimpleEventLog;

let result = await data.query('start', 'end');

expectQueryResult(result, 0n, true, 0);

result = await data.query('snapshot', 'end');

expectQueryResult(result, 0n, true, 0);

result = await data.query(0n, 0n);

expectQueryResult(result, 0n, true, 0);

result = await data.query(0n, 5n);

expectQueryResult(result, 0n, true, 0);

...

}

}

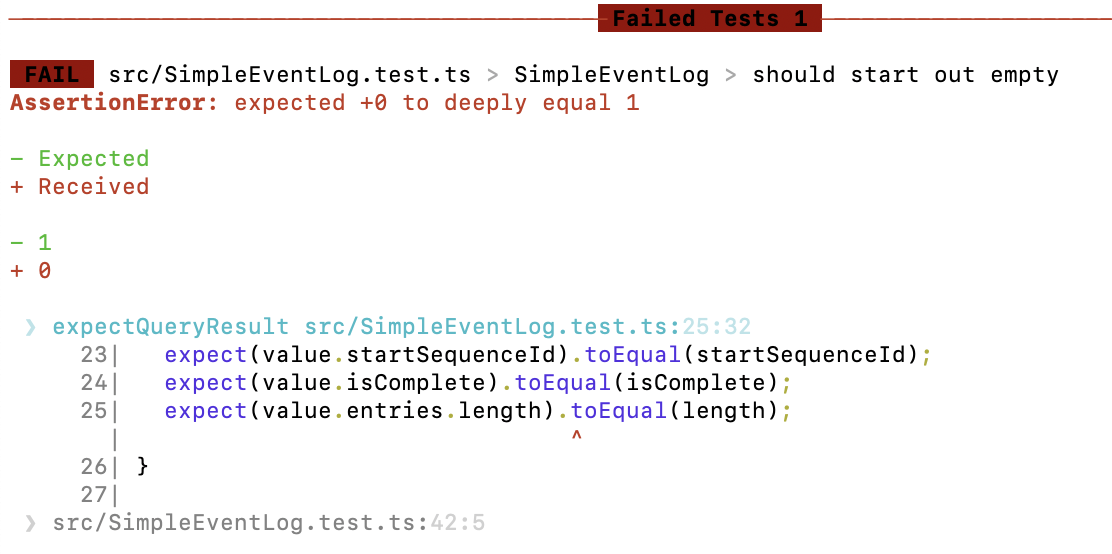

That looks much cleaner. However, remember what I said about the code being shaped by the tooling? Let’s see what happens if I change the arguments to one of the expectQueryResult calls, causing the test to fail.

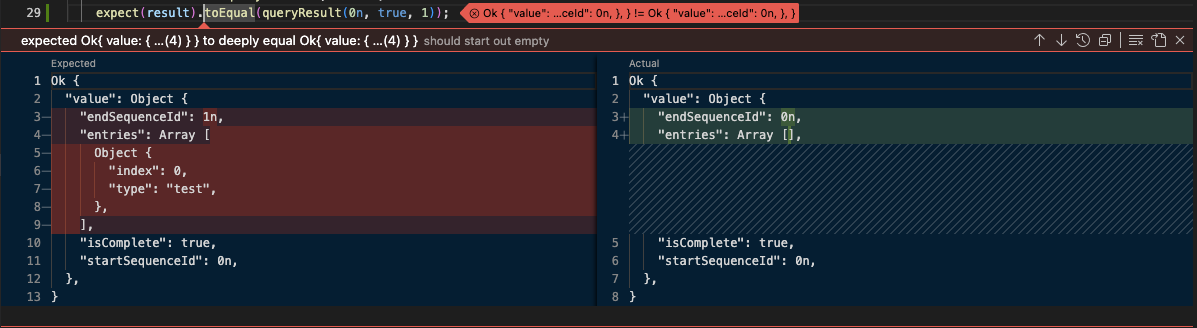

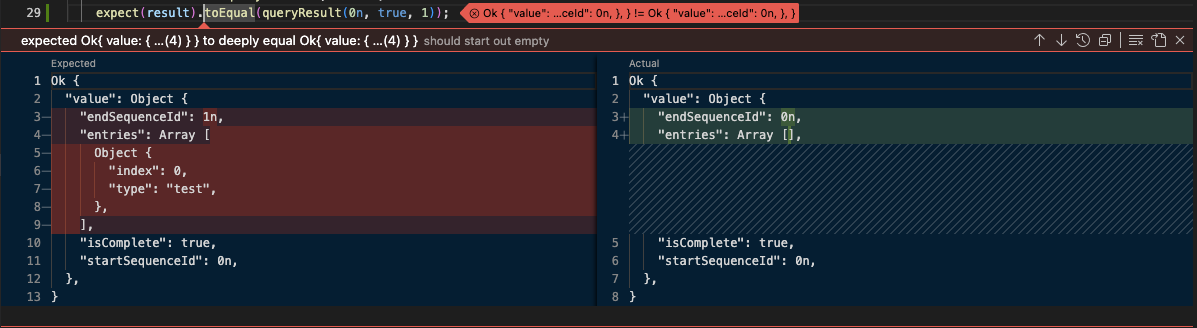

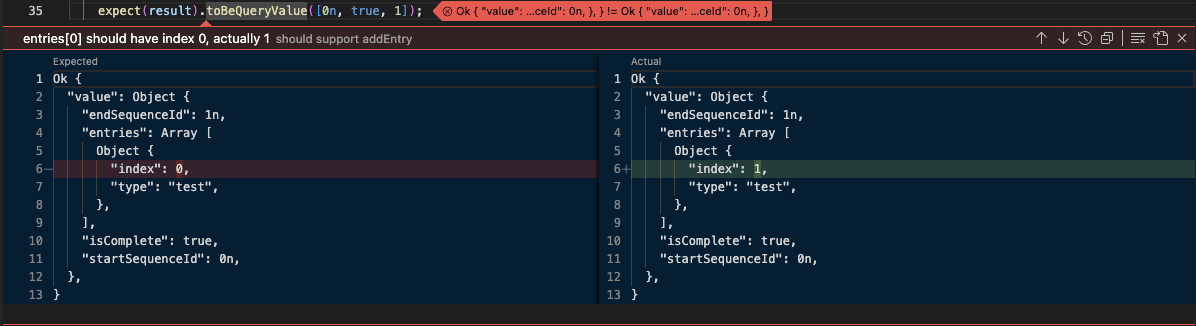

The standard Vitest tooling reports the error on the failing assertion inside expectQueryResult. There’s nothing to tell me which line of the test failed. That can turn a quick fix into the annoyance of having to run a test under the debugger to find out where the problem actually is.

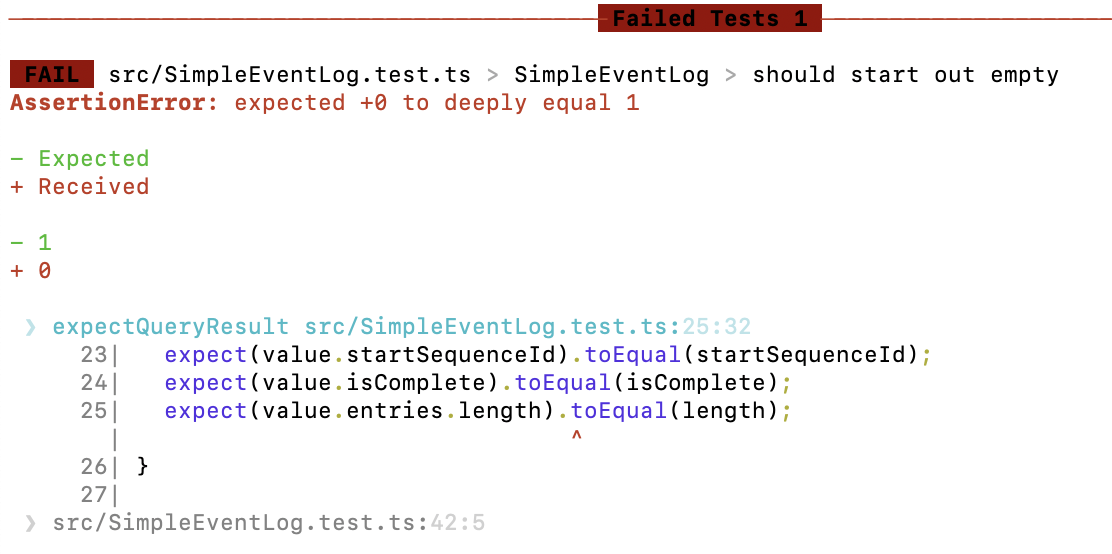

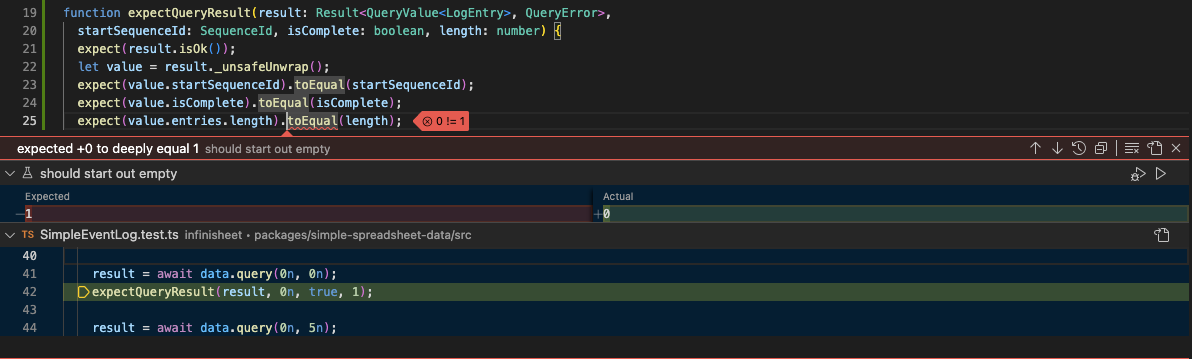

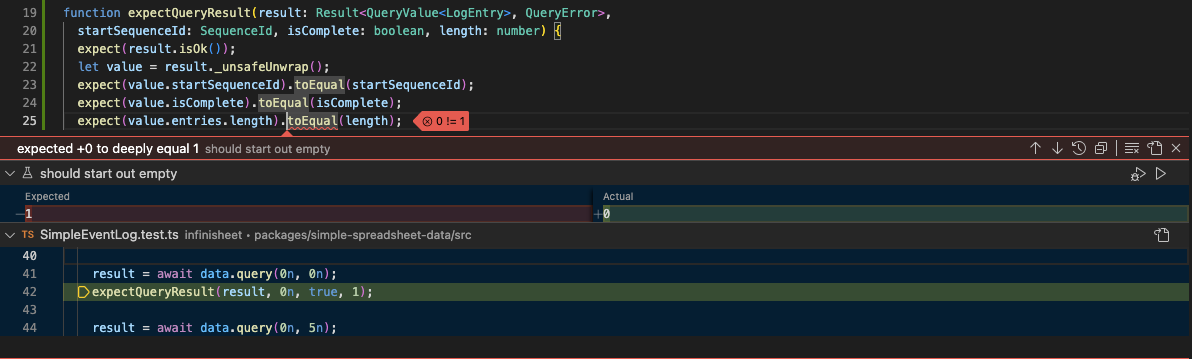

You get better results when using the Vitest plugin for VS Code.

The initial error marker is also inside expectQueryResult. However, if you click on it for more detail, you’re shown the failing line in the test. Not ideal, but usable.

Deeply Equal

In general, you get the most consistent results from unit test tooling if all the expect assertions are at the top level of each test. If you follow this principle, your only option for making tests less verbose is to use fewer assertions.

In our case, we’re testing a query method which returns a QueryValue object in a Result wrapper. We use five lines of assertions to check individual properties of the QueryValue and Result.

One trick you can use is to extract a utility method that creates an object with the properties you expect, then use the toEqual assertion which does a deep comparison of the objects.

function queryResult(startSequenceId: SequenceId, isComplete: boolean, length: number): Result<QueryValue<TestLogEntry>, QueryError> {

const value: QueryValue<TestLogEntry> = {

startSequenceId, isComplete,

endSequenceId: startSequenceId + BigInt(length),

entries: []

};

for (let i = 0; i < length; i ++)

value.entries.push({ type: 'test', index: i });

return ok(value);

}

describe('SimpleEventLog', () => {

test('should start out empty', async () => {

const data = new SimpleEventLog;

let result = await data.query('start', 'end');

expect(result).toEqual(queryResult(0n, true, 0));

result = await data.query('snapshot', 'end');

expect(result).toEqual(queryResult(0n, true, 0));

result = await data.query(0n, 0n);

expect(result).toEqual(queryResult(0n, true, 0));

result = await data.query(0n, 5n);

expect(result).toEqual(queryResult(0n, true, 0));

...

}

}

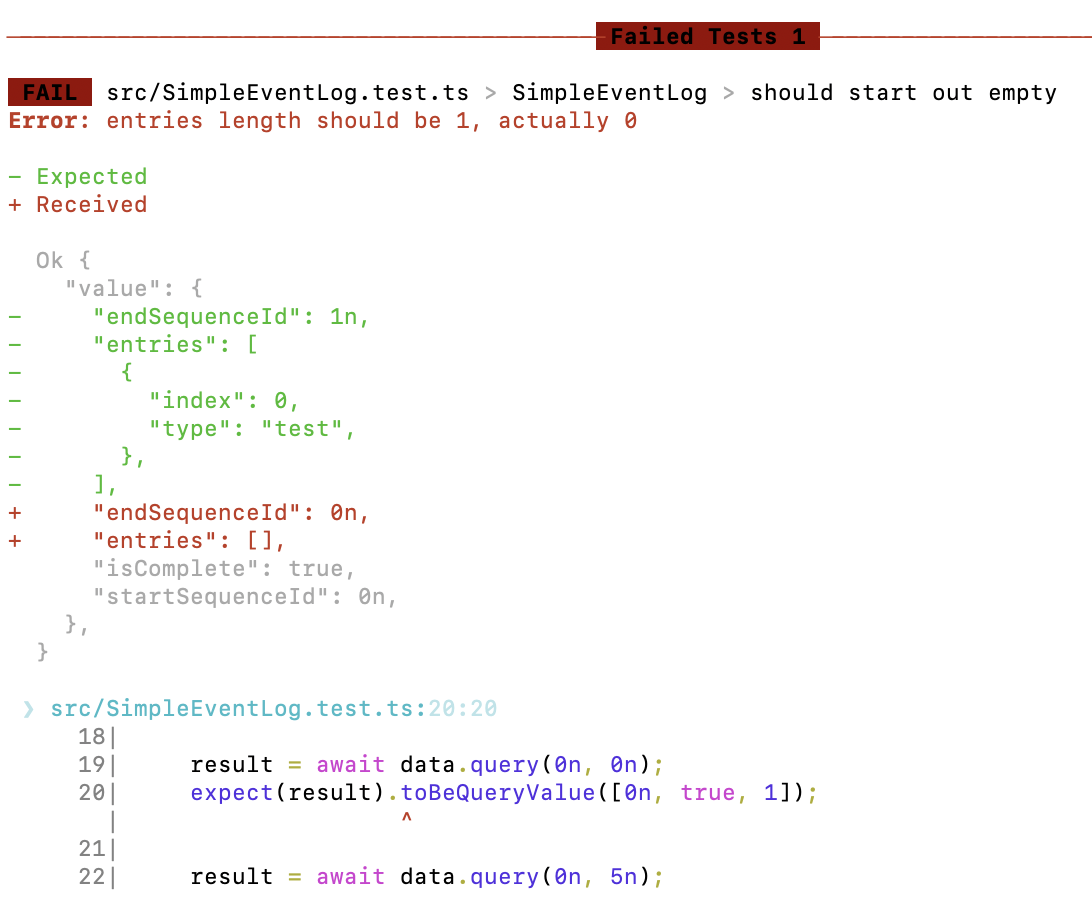

The test code looks just as clean as before, but now all the tooling reports the error in the right place.

Unfortunately, the one line summary of the error is not helpful. It tells you that a comparison has failed between two complex objects but that’s about it. However, both the standard tooling and VS Code plugins include a more detailed side by side comparison of the objects.

Custom Matchers

Can we do better? Yes, if we’re prepared to put some effort in. Vitest allows you to extend the set of matchers available to use with expect.

function fail(message: () => string, _actual: unknown, _expected: [SequenceId, boolean, number]) {

return { pass: false, message } }

}

expect.extend({

toBeQueryValue(received: Result<QueryValue<TestLogEntry>,unknown>, expected: [SequenceId, boolean, number]) {

const [startSequenceId, isComplete, length] = expected;

if (!received.isOk())

return fail(() => "Should be Ok", received, expected);

const value = received.value;

if (value.startSequenceId !== startSequenceId)

return fail( () => `startSequenceId should be ${startSequenceId}, actually ${value.startSequenceId}`, received, expected);

if (value.isComplete !== isComplete)

return fail( () => `isComplete should be ${isComplete}, actually ${value.isComplete}`, received, expected);

if (value.entries.length != length)

return fail(() => `entries length should be ${length}, actually ${value.entries.length}`, received, expected);

if (value.endSequenceId !== startSequenceId+BigInt(length))

return fail(() => `endSequenceId should be ${startSequenceId+BigInt(length)}, actually ${value.endSequenceId}`, received, expected);

for (let i = 0; i < length; i ++) {

const entry = value.entries[i]!;

const expectedIndex = Number(startSequenceId)+i

if (entry.index != expectedIndex)

return fail(() => `entries[${i}] should have index ${expectedIndex}, actually ${entry.index}`, received, expected);

}

return { pass: true, message: () => "" }

},

toBeInfinisheetError(received: Result<unknown,InfinisheetError>, expectedType: string) {

if (!received.isErr())

return { pass: false, message: () => "Should be Err" }

const actualType = received.error.type

return { pass: actualType === expectedType, message: () => `error type should be ${expectedType}, actually ${actualType}` }

}

})

These are custom matchers which define toBeQueryValue and toBeInfinisheetError assertions. Each matcher is a function which takes a received value (the argument to expect) and an expected value (the argument to the assertion). You run whatever comparison logic you want and return an ExpectationResult object. The required properties are a pass boolean and a function that returns an error message. My matcher uses a fail utility function to construct expectation results.

You would normally define all your custom matchers as shared utility code. If you include the utility source file in your Vitest setupFiles config, it will be run automatically before each test file. This way, just like the built-in assertions, your custom assertions are available in any test file without having to explicitly import anything.

You also need to provide typings, otherwise TypeScript will complain when you try to use your assertions. Copy the boiler plate from the Vitest documentation and include a line for each of your matchers. As long as your *.d.ts typing file is included by your tsconfig.json, it will be used automatically.

interface CustomMatchers<R = unknown> {

toBeQueryValue: (expected: [SequenceId, boolean, number]) => R

toBeInfinisheetError: (expectedType: string) => R

}

declare module 'vitest' {

interface Assertion<T = any> extends CustomMatchers<T> {}

interface AsymmetricMatchersContaining extends CustomMatchers {}

}

Once all that’s done you can write tests like this.

describe('SimpleEventLog', () => {

it('should start out empty', async () => {

const data = creator();

let result = await data.query('start', 'end');

expect(result).toBeQueryValue([0n, true, 0]);

result = await data.query('snapshot', 'end');

expect(result).toBeQueryValue([0n, true, 0]);

result = await data.query(0n, 0n);

expect(result).toBeQueryValue([0n, true, 0]);

result = await data.query(0n, 5n);

expect(result).toBeQueryValue([0n, true, 0]);

result = await data.query(5n, 30n);

expect(result).toBeInfinisheetError("InfinisheetRangeError");

result = await data.query(-5n, 0n);

expect(result).toBeInfinisheetError("InfinisheetRangeError");

})

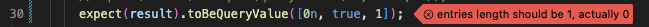

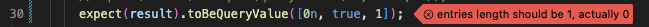

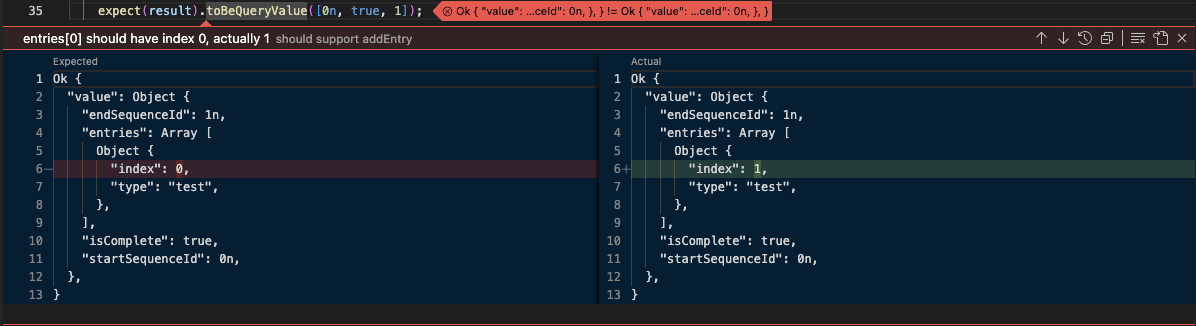

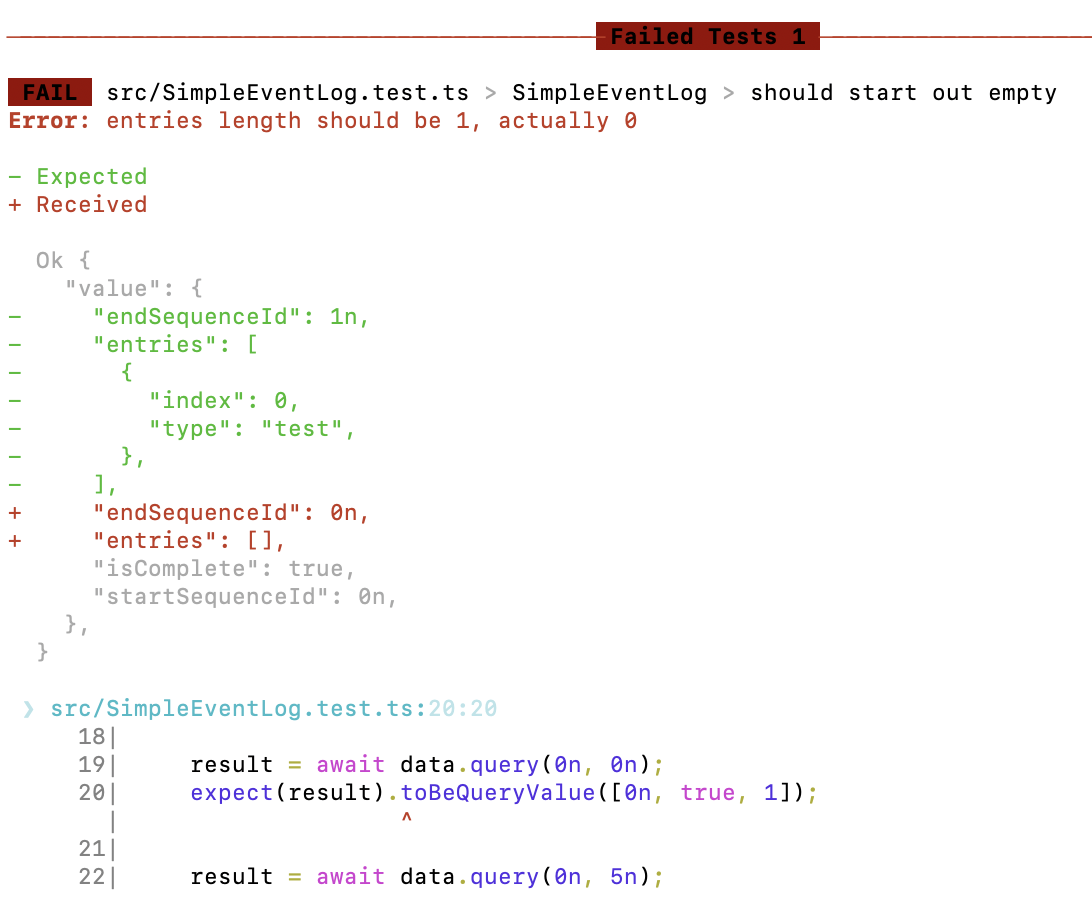

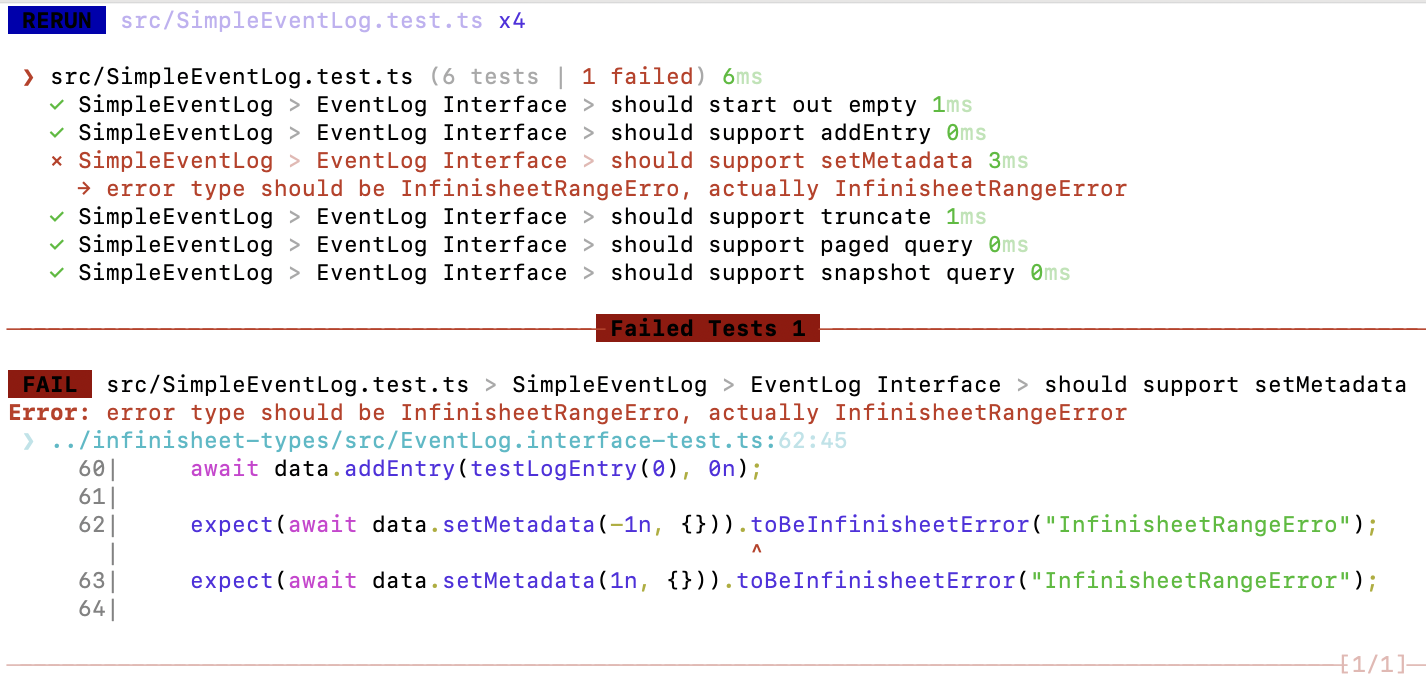

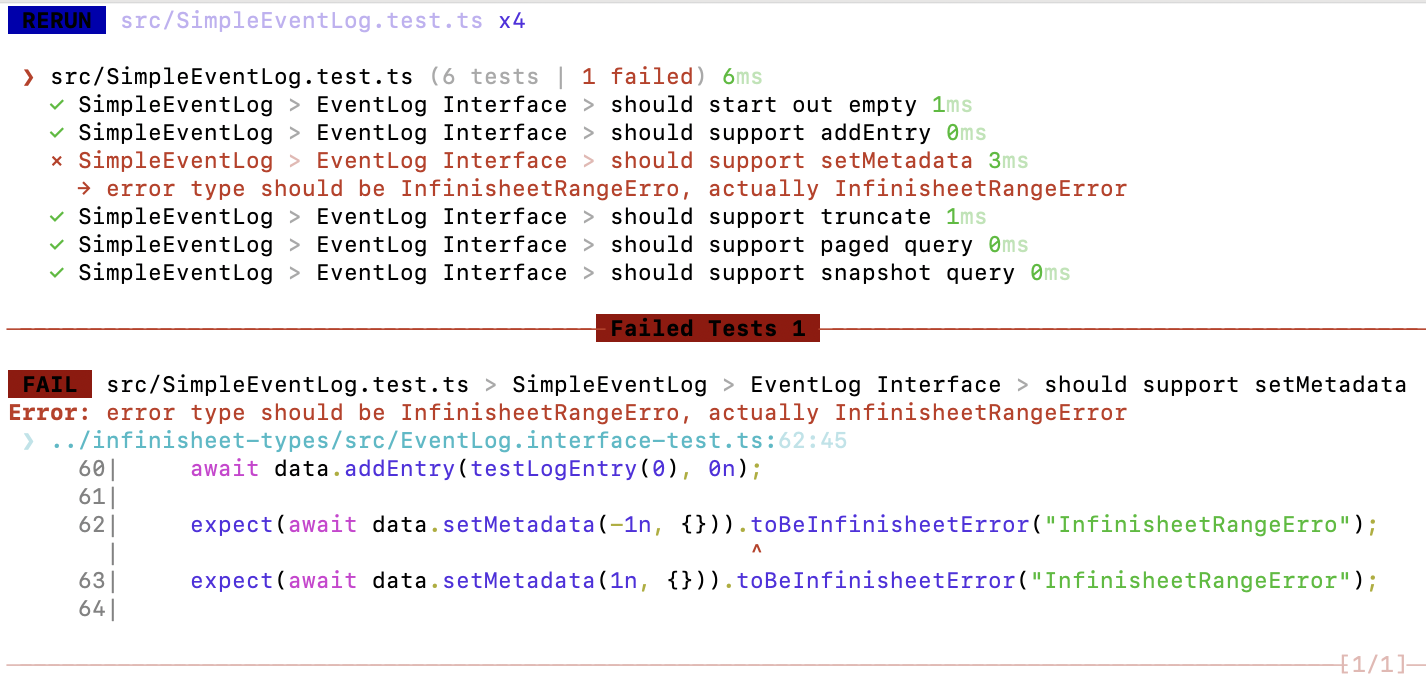

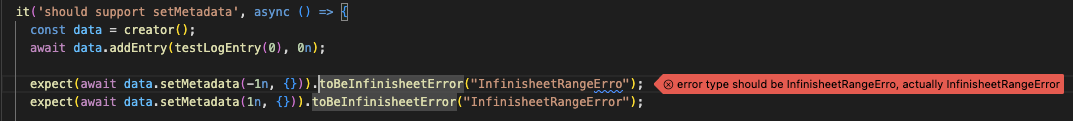

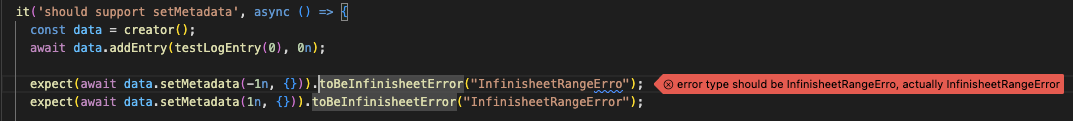

And receive informative errors like this, in exactly the right place.

The ExpectationResult interface has another trick up its sleeve. There are optional actual and expected properties. If provided, unit test tooling can provide a detailed comparison of the difference between them.

function fail(message: () => string, actual: unknown, expected: [SequenceId, boolean, number]) {

const [startSequenceId, isComplete, length] = expected;

return { pass: false, message, actual, expected: queryResult(startSequenceId, isComplete, length)} }

}

Given a suitably updated fail function, VS Code will now produce this.

Snatching defeat from the jaws of victory. For some inexplicable reason, the Vitest plugin has decided to use the incomprehensible object comparison summary as the main error message, rather than the carefully crafted message provided by the matcher. However, if you expand to show the detailed comparison, it will show you the right message.

In contrast, the standard command line tooling does the right thing.

Interface Tests

The SimpleEventLog class is a reference implementation of the EventLog interface. There are multiple implementations with different backends. Initially, I had dedicated unit tests for each implementation. Unsurprisingly, there was lots of overlap. If these are implementations of the same interface, then they should all have behavior that meets the expectations of that interface.

Ideally, I would have a unit test suite for the interface that effectively defines the contract for its behavior. I could then run the interface tests against each implementation to check that they comply with the contract. Each implementation can have additional tests for any unique behavior.

My first thought was to use context properties and projects. However, that seems like overkill. There’s so much configuration and complexity to manage. Then I came across this article, and in particular the section on shared test suites.

Test suites and tests are just nested function calls. The framework uses the sequence of calls to describe and test to work out the overall structure. You can nest suites by calling describe inside another describe. There’s no requirement that all this is contained in a single file. You can wrap an entire test suite in a function and export it so that it can be reused.

export function eventLogInterfaceTests(creator: () => EventLog<TestLogEntry>) {

describe('EventLog Interface', () => {

test('should start out empty', async () => {

const data = creator();

let result = await data.query('start', 'end');

expect(result).toBeQueryValue([0n, true, 0]);

...

})

...

})}

I removed direct dependencies on specific implementations by passing in a creator function. Each test calls the creator to create an instance of the interface to be tested. Add extra arguments if you need them. You have complete flexibility in how configurable you make each reusable test suite.

I refactored my unit tests so that all common tests for the interface are in EventLog.interface-test.ts. I tweaked my tsconfig.json so that interface tests are not run directly while also being excluded from package builds. Each implementation imports and runs the interface tests as a nested test suite.

import { eventLogInterfaceTests } from '../../infinisheet-types/src/EventLog.interface-test'

describe('SimpleEventLog', () => {

eventLogInterfaceTests(() => new SimpleEventLog<TestLogEntry>);

// SimplEventLog specific tests go here

})

It works perfectly with the standard tooling. You can see the nesting of the test suites in the report, so you know where you are. The detailed error report shows you the failing assertion in the nested interface test suite.

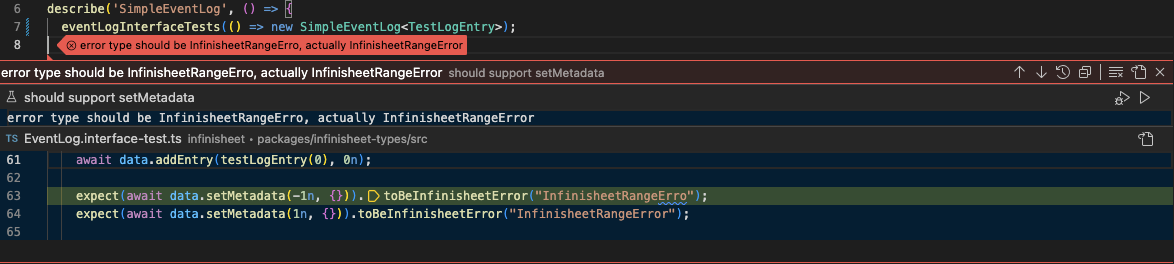

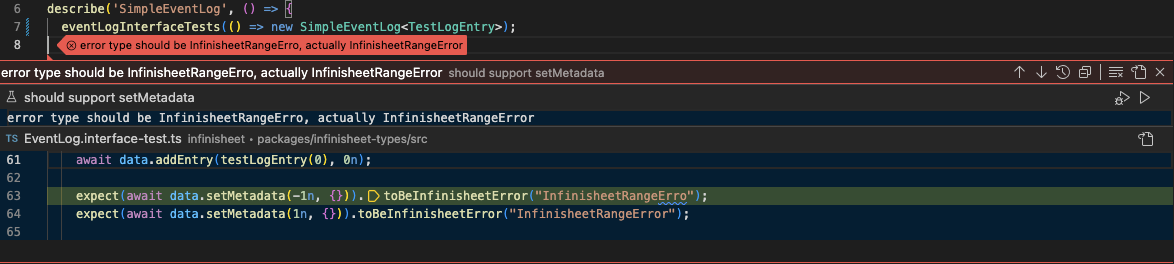

The VS Code plugin has its own way of reaching the same ends. The error summary is reported against the call to the nested test suite in the implementation test file, so you know the overall context of where you are. If you click for more detail, you see the relevant lines from the nested test suite.

Finally, if you click on the open in file icon to the right, VS Code will take you to the interface test file and show you the error in context.

Conclusion

Unit test code is its own particular thing, driven by the expectations of your unit test framework’s tooling. However, that doesn’t mean you have to throw abstraction out of the window and resign yourself to copy and paste hell. There’s lots of ways that you can abstract and reuse test code that will still play nicely with your tooling.